High Ridge Lookout

High Ridge Lookout, elevation 5,303 feet, Walla Walla Ranger District, Umatilla National Forest, Oregon. Six miles south of Tollgate, reached from Forest Road 31, and spur road 275 which is normally locked.

High Ridge Lookout Tower on the Umatilla National Forest, built in 1959 and still staffed at times.

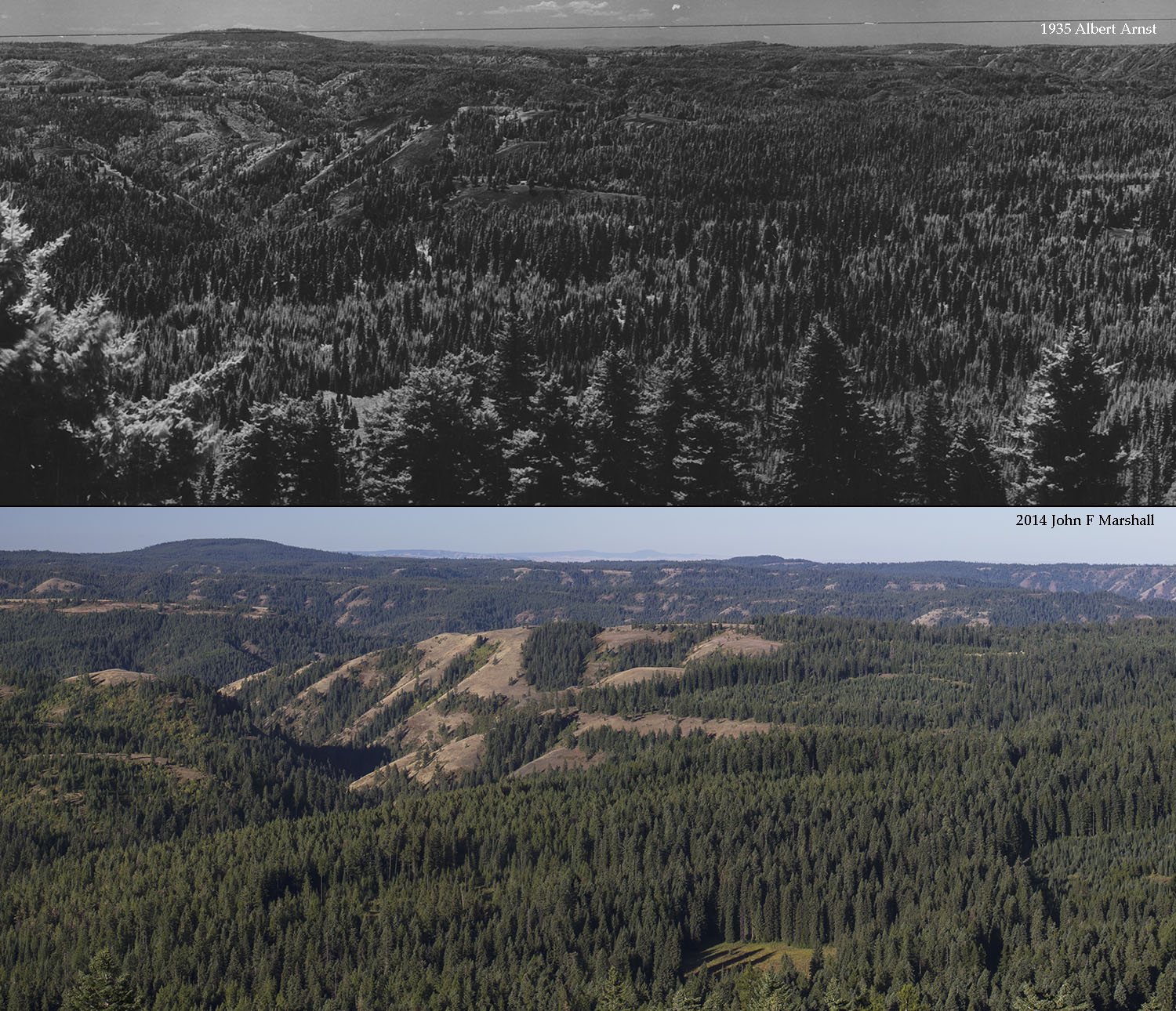

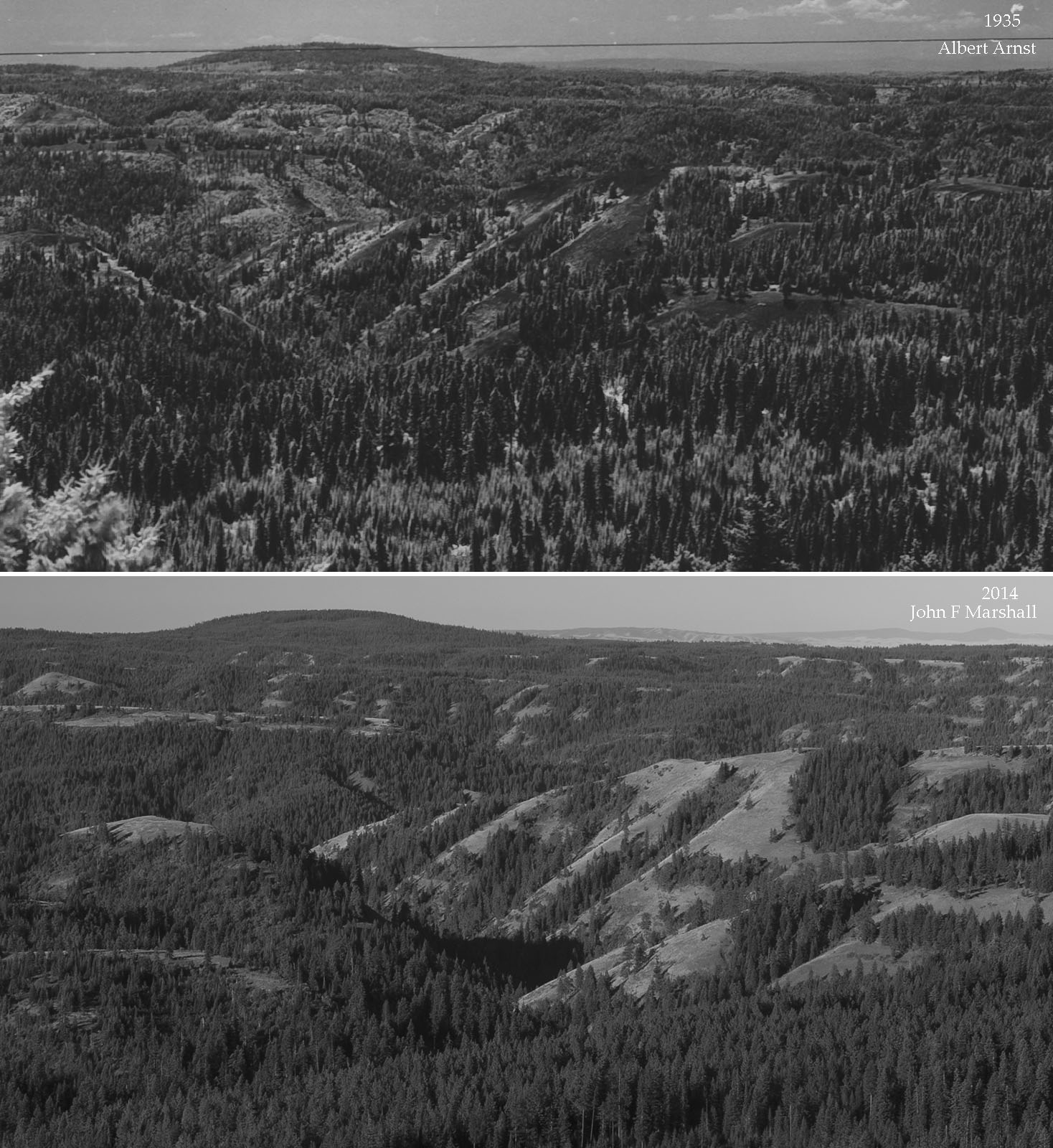

The northern Blue Mountains is a region of highly productive forests. Moisture-laden air coming off the Pacific Ocean funnels through the Columbia River Gorge and as it rises over the Blue Mountains it dumps snow in winter and rain often from thunderstorms in the summer months. This precipitation pattern gives rise to what is known as "moist mixed-conifer forests". Tree species are Douglas-fir, grand fir, western larch, lodgepole pine, ponderosa pine, and Engelmann spruce. The comparison photographs from High Ridge Lookout are instructive in understanding changes to the moist mixed-conifer forests in the Blue Mountains over the past eighty years. Looking at the historic photograph from 1935 and the re-take from 2014, there is a difference of texture and pattern. One has to get past the fact that the original photograph was taken with infrared film, and the re-take was not, and that landscape features are not a perfect match as the tower was moved. Two major influences have occurred: logging and fire suppression.

The photograph from 1935, shows a forest shaped by frequent fire, including patches of high severity fire that killed all of the trees leaving snags. Most of the fire was mixed-severity; killing 25% to 75% of the trees, and most fires were small. On rare occasion there were very large fires, such as the Kamela to Troy fire of 68,000 acres in the 1850s. On south-facing slopes at the lower elevations, frequent low severity fire in ponderosa pine was the norm. Then there were re-burns, where fire went through patches of young trees inter-laced with logs, in conditions that happened ten to thirty years after the initial fire. It all added up to a very complicated mosaic of vegetation with open areas favoring sun-loving plants and closed canopy forest favoring shade-loving, or shade tolerant plants. Diverse plant communities along with snags and logs supported diverse and robust wildlife populations. Each condition across the landscape met a need for some species at some time in its life history. The irregular edges left by fire and re-burns, along with topography incised by canyons made for a very ecologically diverse region.

Fire suppression largely took fire away as a disturbance agent for about fifty years. Logging- both selective cutting and clear-cutting, became the major influence of change. Selective cutting changed the forest in ways that were not expected. Large mature trees or clumps of mature trees were taken to the mills. The assumption was that the smaller trees left behind would become the large trees of the future. In fact, what typically happened is that the gaps left behind filled in with small trees. Absent the presence of fire or thinning by chainsaw, the small trees live in a crowded condition where they grow poorly and are susceptible to insects and disease. Thinning sapling trees is a cost of doing forestry, which has no immediate pay-off hence many areas across the west are neglected, whether it be federal, state, or private land.

1935 USFS photo by Albert Arnst from the National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. Bottom photo by John F Marshall from 2014 funded by Umatilla National Forest through Wenatchee Forestry Sciences Lab.

Above- The comparison photos are less than a perfect match due to the fact that the original panoramic photograph taken by Albert Arnst in 1935 was from a tower that no longer exists. The present day 67- foot tall tower was built in 1959, and is to the east of the original 24- foot tower. Also a factor is that the original photograph was taken with infrared film, reversing some of the tones, when compared to the re-take.

Above- Comparing photographs, the present day forest has a dense and more uniform feel that is particularly evident in the black & white on black & white comparison. At first glance the "balds" grassy rocky slopes without trees stand out more in the 2014 photo. That may be attributed to the use of infrared film in the 1935 photo. It also true that range conditions have improved since 1935, having had time to recovery from intense sheep grazing in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Above- It is easier to grasp the changes, when looking at a portion of the landscape rather than the whole. Gone is much of the open area to the left of center that was in shrubs and grasses in 1935. Round Mountain, four miles distant at top left, looks very different. There are more trees just about everywhere, and they appear to be be younger and smaller on average. Un-apparent at the scale of the photograph is that the species mix has changed also. Grand fir is a tree native to the Blue Mountains that tolerates fire very poorly as a seedling and sapling tree. As a mature tree it can handle some fire. What it does tolerate well is shade. Under the influence of shade and in the absence of fire, grand fir has been allowed to proliferate in places where historically it was very limited.

Above- Clear-cut logging, followed by planting of favored tree species was a common practice in the moist-mixed conifer forests of the Blue Mountains in the nineteen seventies and nineteen eighties. An industrial model of efficiency displaced ancient patterns. Now clear-cutting has been largely abandoned by the U.S. Forest Service in favor of methods that leave residual trees.

While both wildfire and clear-cutting open up patches of forest to sunlight, promoting grasses, and shrubs that benefit deer and elk, there are big differences. Wildfires, if unbounded by fire-lines and roads, burn in irregular patterns, and at varying intensities, leaving behind a ragged edge, instead of something that looks like it was sliced out of the land with an exacto knife. The other main difference between a clear-cut and a burn is the presence of large numbers of snags and logs. Snags are important to cavity nesting birds, such as blue-birds, swallows and woodpeckers, and as resting sites for hawks and eagles. As logs decay they become important to plant growth. Logs hold moisture and are sites for mycorrhizae fungi to establish, which in turn feed nutrients to trees through root connections. Today a more sensitive practice known as restoration forestry is being adopted, that targets small and medium size trees to be cut and sent to the mills, leaving in place the larger trees remaining from the hay-day of logging. The idea is to create space between trees, and space between clumps of trees, re-shaping the landscape to be less vulnerable to both wide spread fire and insect epidemics.

Penstemon and yarrow growing on lithosol soils in the Blue Mountains, Umatilla National Forest.

The Blue Mountains were a beautiful and interesting place in the 1930s, and are still a beautiful and interesting place! Thanks to Dave Powell and Paul Hessburg for some critical edits!