Mills Canyon Reburn

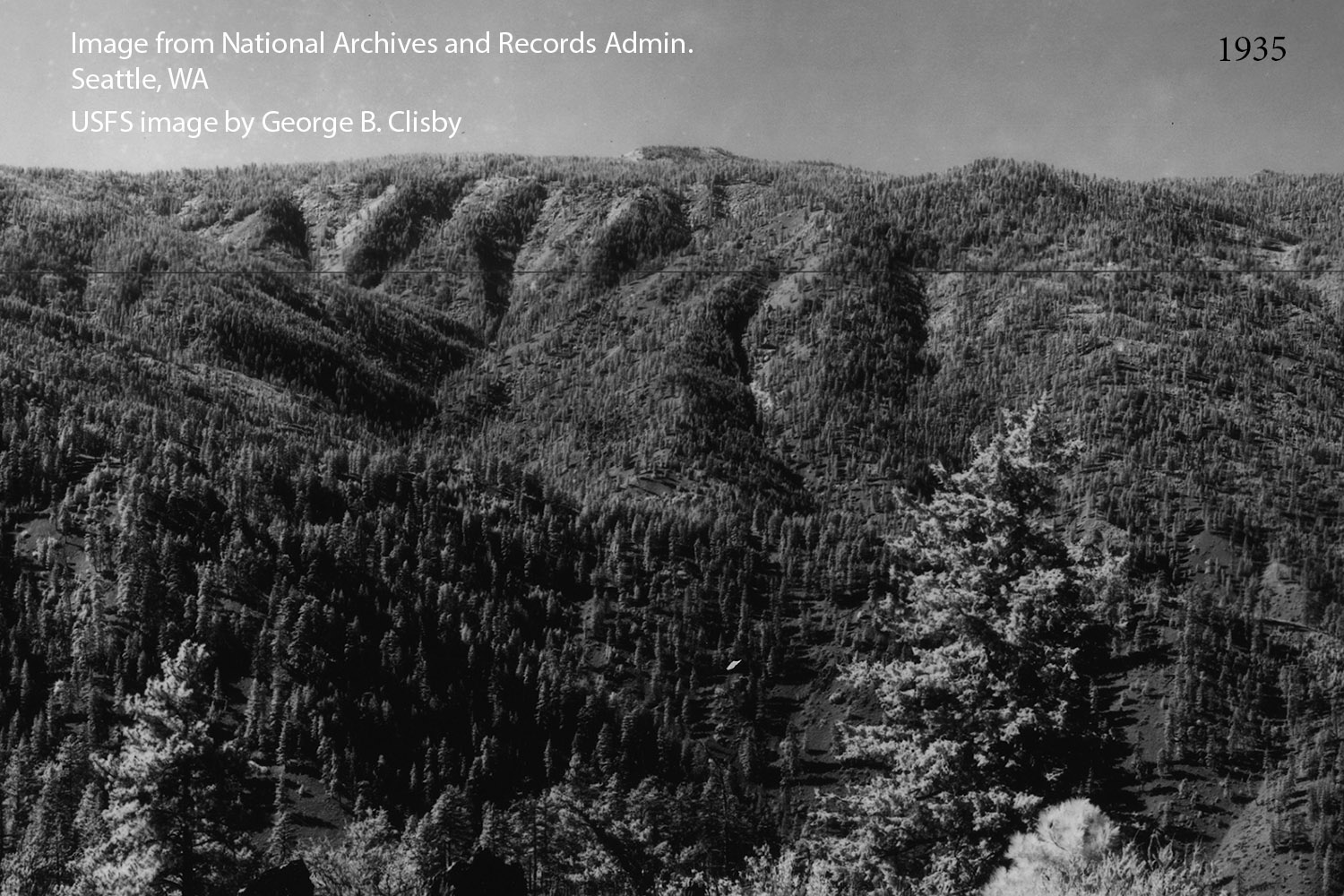

Mills Canyon is located three miles up the Entiat Valley in North Central Washington. It is part of the Entiat Ranger District of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. Historical photos of the Entiat from the 1930s show an open forest, dominated by ponderosa pine. Today, Mills Canyon has large expanses with little or no trees- only brush. Clear-cut logging did not happen here. The deforestation one sees in Mills Canyon is caused by two wildfires- one in 1988 and one in 2014. In a theme that keeps replaying through-out the west, a forest gone too thick burns in a spectacular way, leaving few live trees.

Dinkelmann Fire in 1988, burned through all of Mills Canyon. Salvage logging did occur, but many of the dead trees were left standing as snags. Snags are important for wildlife habitat, particularly the larger ones. The Forest Service replanted Mills Canyon, and the young trees were doing well when Mills Canyon was hit by a second fire in 2014. The combination of small green trees, flammable shrubs, and small diameter logs left over from the Dinkelmann Fire was a molotov cocktail. Very few of the young trees survived the fire. Fire weather was extreme at times during the 2014 event. In some places large, older trees that would normally be thought safe, also died in the fire.

Top photo- Mills Canyon in 1935 from the Osborne Panoramic collection, accessed from the National Archives and Records Administration in Seattle. Bottom photo- Mills Canyon as it was in September of 2016. The next two images provide a close-up comparison.

- Smoke column from 1988 Dinkelmann Fire burning in the Entiat River drainage as seen from the Wenatchee Valley side of the Entiat Mountains near Peshastin.

- In 2011, Mills Canyon was largely acres of shrubs with Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine trees emerging. The creamy-flowered shrub is red-stem ceanothus, (Ceanothus sanguineus), a plant favored by deer and elk for browsing.

- The same view as above on August 8, 2014 one month after Mills Canyon Fire. All of the young fir and pine trees in the foreground are dead.

- In less than two years time, Mills Canyon made an amazing recovery. Far from being dead the shrubs re-sprouted from below ground roots, not so the trees. June 1, 2016

- Charred remnants from the prior forest punctuate a shrub-filled canyon bottom. Conifers such as the ponderosa pine at lower left, would eventually shade out the shrubs, had there not been another fire. 2011 photo

- All was lost, it would seem from looking at this photograph taken one month after Mills Canyon Fire of 2014.

- All was not lost. The shrubs which include Douglas-maple, red-stem ceanothus, and willow were only killed above ground. The roots survived beneath the soil, and sent up vigorous new growth. Left behind are dead conifer trees. June 2016.

- Moonscape appearance of a hillside, one month after the Mills Canyon Fire in 2014.

- The same scene as above, on June 1 of 2016- nature has done an amazing job of restoration. Apparently the soil was not as lifeless as it looked.

One is left wondering whether Mills Canyon will ever return to the forest shown in the nineteen thirties photograph? As the climate warms up, will fires fall in such quick succession that young trees are killed before they can fully grow? That is possible. Chaparral is the term used to describe an area that could support forest but does not, because of repeated burning. Chaparral may be in the future for Mills Canyon. One way to look at it is that chaparral has its own beauty. However, the assemblages of plants and animals living in chaparral are much more limited compared to what occurs in a forest interspersed with openings.

The tree best adapted to living here in a warming climate is the ponderosa pine. Too few have survived the fires, making for a long distance between trees. Seeds from cones will produce young trees, but the distance of dispersal is limited. If there is any hope for Mills Canyon as a forest, it will be through tree planting, thinning, and prescribed fire. That takes human commitment.