Tom Dick Mountain

Tom Dick Mountain is located three miles southwest of Government Camp on the south side of Highway 26. One can get there by taking the trail to Mirror Lake, continuing to the ridge-top where the maintained trail ends, and then walking on primitive paths further east for about half a mile. The lookout cabin there, built in 1933 was destroyed in 1949. This high point is also known as Tom Dick and Harry Mountain and Tom Dick Ridge.

An extensive fire burned the forested area south and west of Mt. Hood around 1910, killing most of the trees over large areas. Large fires in this cool wet environment were historically very uncommon and only happened under drought conditions. Fire typically visited any one spot on the order of every several hundred years. Fire return intervals were much longer in wet boggy places, and more frequent on south and west facing slopes. Lightning lit small fires on the drier slopes with a fair frequency, but they typically did not burn very far, before reaching places where conditions did not allow further burning. The other factor was Indian burning. The forest below Mt. Hood as seen in the 1933 picture shows vegetation patches at different stages of recovery from fires. Indians intentionally set fires to maintain huckleberry fields, an important food and aspect of native culture even today. Huckleberries due best in openings, where they get ample sun, and under heavy shade they produce few berries, and may die out. The Mt. Hood area was a fabulous place to pick huckleberries at the time of the 1933 Osborne Panorama. My father's family went out with buckets to pick them, and I remember open huckleberry fields in the sixties as a kid that are now completely shaded out. There are still huckleberries on the south side of Mt. Hood, but the picking opportunities are diminished.

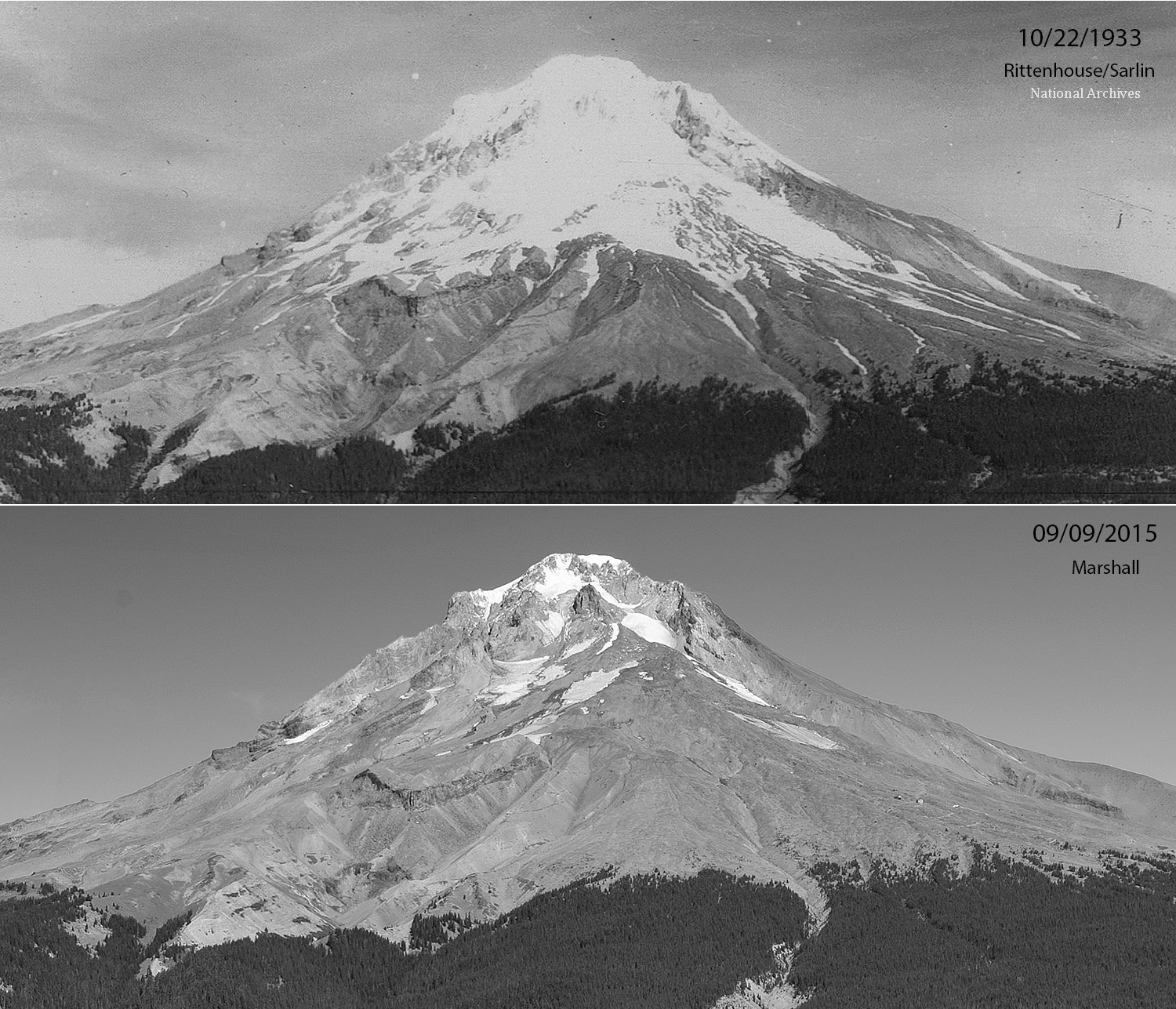

Top Image- James D. Rittenhouse and Reino R. Sarlin 10/22/1933 from the National Archives and Records Administration in Seattle, WA Bottom Image-John F Marshall

The village of Government camp can be seen in the upper right of both photos. While "Govy" has changed in eighty years, the vegetation has changed even more. Meadows and shrub-fields have given way to forest. No doubt fire will return to the south side of Mt. Hood, as it has the north side in recent years. It will be good for some plants and animals and bad for others. The potential for property loss is high. However you want to slice it, the broad continuous expanse of green trees today, is not a permanent fixture, and never was. Fire ebbs, and flows, and meadows, trees, and huckleberries go along with it. At any one period of time, there was more meadow, or more forest. There has been a loss of ecological diversity, due to many decades of successful fire suppression, as evidenced by the two pictures. Some small fires over the past hundred years would have made the landscape more diverse. The lack of meadows and shrub-fields, also means that a fire under extreme drought and weather conditions will be harder to put out, as the fuels are now continuous.

The above photograph taken at Mt. Rainier National Park thirty years ago, represents the kind of post fire environment that I remember from the south side of Mt. Hood as a boy.

Climate change comes to mind with this pair of pictures. Granted, the historic picture was taken in late October after an early snowfall, and the 2015 photograph was taken in early September before the first snowfall. However, the large expanses of snow without rocks showing, indicate that glacier ice was beneath the snow in many places, in the 1933 photograph. Had the snow not fallen on top of ice, there would be more bare areas. The 2015 photo is noticeably sharper and more detailed in spite of being shown at the same resolution. Camera lenses have vastly improved since 1933.