Windy Peak, 8,334 feet elevation, Pasayten Wilderness, 17 miles NW of Loomis in Okanogan County, WA. Seven miles by Trail 342 (Horseshoe Basin), starting at Long Swamp Campground, Forest Road 39.

The way in to Windy Peak on Trail 342.

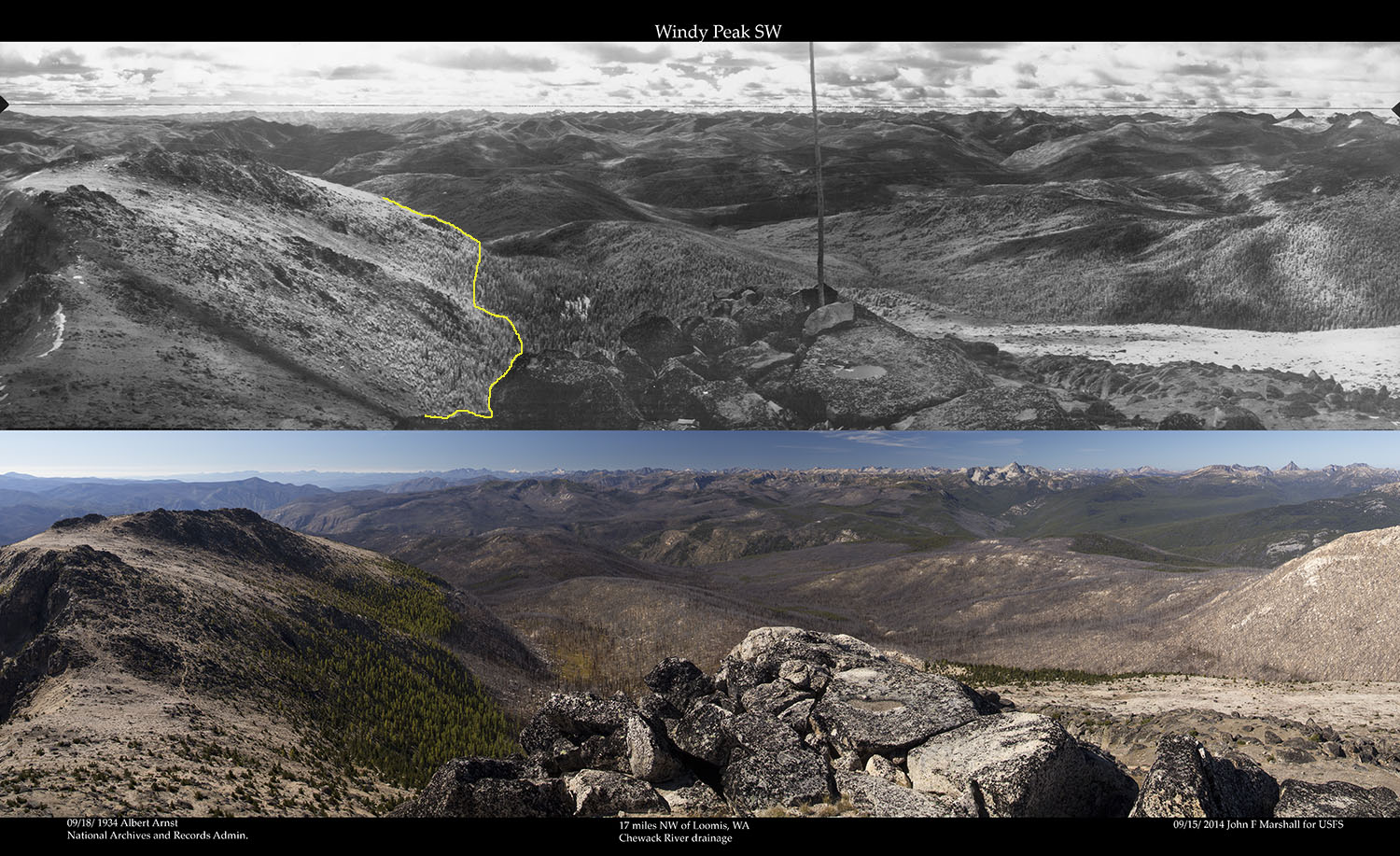

In 2006 Tripod Fire burned through 175,000 acres in Okanogan County. Much of it was in high elevation forest dominated by lodgepole pine, subalpine fir, and Engelmann- spruce. The historic photo comparison of Windy Peak SW below, illustrates an important principle of fire behavior. The area to the left of the yellow line drawn on the 1934 photo, is a very young stand of alpine larch, initiated by a fire, perhaps around 1915. The early fire would have removed all of the fine fuels, leaving behind snags. Roughly ninety years later in 2006, Tripod Fire stopped at the old fire boundary, due to insufficient fuels. There no doubt were logs on the ground, but not a large accumulation of smaller fuels. The fire of circa 1915 still had an influence after nine decades. This might not hold up everywhere, but in this cold and fairly dry environment, plant growth is limited. Often fire managers look to old burn scars as places where they might be successful in halting the advance of a wildfire. Put another way, small fires are important in preventing really large fires.

WINDY PEAK SW 1934 Photo- Albert Arnst from National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, Wa. 2014 Photo- John F Marshall for Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest and Wenatchee Forestry Sciences Lab. View looking from 180 degrees (south) to 300 degrees (west by northwest) Yellow line shows boundary of old fire scar.

WINDY PEAK SE 1934 Photo- Albert Arnst from National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. 2014 Photo- John F Marshall for Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest and Wenatchee Forestry Sciences Lab. View looking from 60 degrees (east by northeast) to 180 degrees (south).

Tripod Fire of 2006 burned through vast expanses of forest, leaving few live trees in it's wake. This is in contrast to how fires typically burned in the past. The difference is apparent, when one zooms in on the photos. The two crops were taken from the left one third of the panoramas. Although the 1934 photo is fuzzy, it shows a highly complex mosaic of vegetation resulting from fire burning at different times and intensities. Looking at the same area in the 2014 photo there are no live trees to be seen. Between persistent wind and the blurring of old fire scars, the fires of today are often times unlike the fires of the past. So much of the outcome of fire is weather dependent. When fire weather is moderate, then the outcome of a wildfire can be quite favorable, on the other hand hot, dry, windy conditions typically lead to all-around poor outcomes.

From an ecological perspective, both burns and closed canopy forests have something to offer plants and animals. The greatest number of species are served, when there is a mixture of habitats. Both the burned area, and the closed canopy forest have something to offer. Even within a single species, there are benefits to having multiple habitat conditions, within close proximity to each other.

Eight years after the Tripod Fire of 2006, the ground is well covered by sun-loving plants including fireweed, grasses, and willow. Lodgepole pine seedlings are well established. Wildlife species that browse willow, feed on grouse berries, or eat seeds will find more to eat here in the summer than in the closed canopy forest.

An un-burned area close to the above photo of a burned area. Under the forest canopy, wildlife can find shade and cover. Shade loving plants thrive here. In winter subalpine fir trees provide subsistence forage for moose and mountain goats.

Even high severity fire can be an ecological good, but not when it covers a large area with little variation. Biodiversity is lacking in this scene. A point of discussion centers around the subject of fire suppression. If fire suppression, has brought problems upon us, then why continue with fire suppression? The answer is that fire suppression decisions need to take into account the likely outcome. There are times, when aggressive early suppression is absolutely the right choice, and other times it would be better to let wildfire do it's thing.